A client who provides a web proxy service to shield enterprise customers from malware recently hired us to build a documentation system we had proposed to quickly produce content for web presentation. Draft text is shared, edited, coupled to graphics, and automatically tailored for export straight to the web in a smooth, secure process based on free and open-source tools.

The company as a proxy executes customers’ web sessions, removing Flash and other active elements that might contain threats, and then relays the sanitized results to the customers, all without perceptible delay. Their customers need clear instructions for installing the service but when the company approached us, the documentation at hand was a mix of PDFs, Word texts, and a few procedures online, all in need of a thorough technical edit and consistent style and branding. We converted the existing documentation so it would be clearly legible on the company website and structured a system for creating new documents that could be easily uploaded to the website and displayed in any screen format with no need for conversion. We had in mind an infrastructure that would be easy to maintain.

First, we converted the existing documents to plain text and then we used Markdown, a simple mark-up language that provides a syntax for plain-text formatting, to generate the typographic conventions for headings, italics, bold type, numbered lists, unordered lists, and so forth. Moving forward, we developed a consistent style in which documents would appear on the website.

Easy to implement

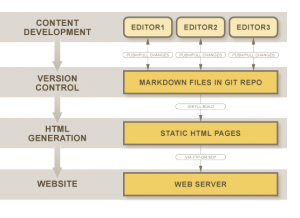

We based the documentation system on a static-site generator—Jekyll–which takes the plain-text files in Markdown, organizes those according to templates we created for text and style, and creates web pages and a navigation hierarchy. Simply run a command and the system produces a directory of files for upload to the web server and the process is complete.

Jekyll is an open-source static-site generator that was intended for blogs as an alternative to WordPress, which was becoming complicated, cumbersome, and involved managing a back-end database. It is extremely easy to use. Features that make it helpful for blogs also make it a very convenient engine for a documentation system. For example, it can automatically create lists of all the blog posts from an author in reverse chronological order and create tags so posts about a particular subject can be collected on one page. We leveraged Jekyll because it thereby enabled building an organizational framework for the documentation system, not only style templates. For fast website deployment, security, and limiting infrastructure maintenance, we decided a static-site generator would best serve the application.

Streamlined workflow

Once we converted the existing documents to plain text, we put them into a private repository on the website Github.com to share and collaborate with the client’s staff. The Github website is based on Git; a version-control system that can pull from many servers. Everyone given company access has their own version of the entire private repository, enabling the staff to work on the files and see each other’s changes.

The client’s chief of publications produced raw content adding to the work we had done, and then we did a technical edit of the new material and submitted changes to him, in an informal ongoing process. However, based on Github, the structure is in place to implement a formal process for merging changes from authors, who can make technical edits and then submit a pull request: I’ve made this change; do you want to accept this into the main branch?

Beyond version control, Github gives a preview of how documents will look. Simply upload a Markdown file with accompanying images and Github melds into order the text and graphics free from compositing symbols. The publication chief can confirm how pages would be organized, set the layout with the Jekyll templates, and commit the results for upload to the company website.

The benefit of using plain text for generating documents, instead of such programs as Framemaker or Word, is that you can tap into the decades of development founded on plain text; namely, all the sophisticated tools that can analyze two very different versions of a text, see where they differ, automatically merge changes, and identify where a conflict must be resolved.

There is some downside of working in plain text, at least for engineers who are documenting product designs in progress. Composing in plain text is not as familiar as writing in Word. However, making the transition from Word to composing in plain text is not especially onerous.

Given the simplicity, convenience, and low cost of using this combination of free and open-source software to build a flexible and robust online documentation system, the approach can benefit many ventures, especially startups who have limited IT resources, small budgets, and pressing calendars.