This is the third of my four events this year. I was exhilarated after completing the Boston Marathon and the California Death Ride. I felt comfortable that my training would get me through the event: My speed work was done while training for the Boston Marathon and my endurance training was done while training for the Death Ride. And most important, I’d gotten through all my training without injury. But I must admit that I was feeling the fatigue from training that had started before Christmas last year. When it came time to tapering for this race, I had no problem taking it easy. I was glad to have the training behind me and looking forward to the reward of racing.

We left San Jose on Tuesday, August 27. I decided to take my Cervelo P2C triathlon bike rather than my Bianchi road bike. Riding a triathlon bike is still new to me, so it’s a risk. It’s harder to steer, and it requires riding in the aero position. If I’m not in shape, my back will be seriously hurting by the end of the ride.

We stopped briefly for lunch at Steady Eddy’s in Winters, CA. The food was good, and Winters is a nice town, not far from Davis. The area looks like a great place to do some bike touring.

Our first overnight stop was Ashland, OR, a town we’ve come to like quite a bit. I like the small college town atmosphere, and Lithia Park is a great place for a morning run. The Black Sheep Pub is a nice place to go for a beer.

From Ashland, we continued up Interstate 5, stopping briefly in Portland for lunch at the BridgePort BrewPub. As it turned out, it’s near to the college that our niece attends. It’s an interesting area, urban/hip with good restaurants, galleries, shopping, that we’ll be sure to re-visit next time we visit Portland. But we still had a long way to go, so we were soon back on the road.

Our next overnight stop was Seattle, where we stayed at the Hotel Andra. We arrived in time for a terrific sunset, which Julie captured nicely in a photo at the Pike Place Market.

In the morning we continued north on I-5 to Bellingham, where we then cut over to Hwy 542 and then Hwy 9, crossing the border at Abbotsford-Huntingdon. It’s been twenty five years since I traveled to Canada, when I drove to Quebec in an early 1970s Ford Pinto with rusted out floorboards . At that time all you needed to get in was a driver’s license. (In our case, that was followed by a thorough search of the car, involving pulling the car over, emptying everything out, a search of the undercarriage using mirrors, etc.)

So naturally, when I pulled up to the Customs Agent this time, I handed her our drivers licenses. The Customs Agent just stared at me, expressionless with those mirror sunglasses. I looked back, I’m sure, with the expression of one who expected that he was about to get pulled over again for a full search.

The tension was broken when Julie leaned over and offered our passports. Lucky for me, because without her I’m not sure I’d be writing about the race. The Customs Agent asked the purpose of our visit, and I said we were going to Penticton. Seeing the bikes on the roof of the car, she asked if we were going to do IronMan Canada. There was still no expression, but I knew we were OK, and she waved us on.

We arrived in Penticton, Canada, late afternoon on Thursday, August 25. It’s a beautiful area, with very large lakes and hills covered with vineyards and orchards. It was a surprise to me to find that it’s a desert climate with 10″ annual rainfall, which is 30% less than what we receive in San Jose. This, of course, means it’s not a forest area. In fact there are very few trees, an observation that would carry much greater importance on race day.

We went first to our hotel, to make sure we had a place and to get our bearings. Most of the hotels during this event required a 5 night commitment, and our hotel was $225/night. (As I write this 4 weeks later, the rate is less than $90/night, no 5-night commitment.)

The joy continued as we next explored the town. It was fine with me, but I could tell it would be a long stay for Julie. There wasn’t much there for her other than a couple of Starbucks coffee shops. We did have a nice dinner al fresco at a recommended restaurant, the Sage and Vines Bistro.

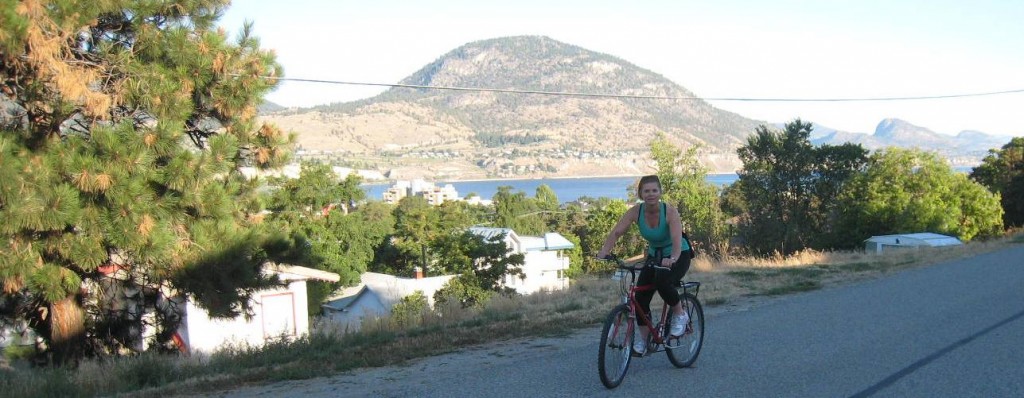

Next morning I went for a short run, with Julie keeping me company on her bike. She’d just had surgery on her knee to fix a meniscus tear. So I was very impressed when she chose to ride up a steep hill. It helped that at the top we got a nice view of the town and the lake.

After a light breakfast at the local Starbucks, it was off to the registration tent to pick up my race packet. We were 45 minutes early, but already there was a line. While we waited I had a nice conversation with Paul Dalton, an ultra-Ironman finisher.

Registration is a mini-event in itself. Once you’re in the tent there are a series of stations to go through, as you prove who you are, sign disclaimers that you won’t sue if you die, get tagged so they can identify the body, confirm your sex by picking the appropriately colored swim cap ( blue for male; pink for female – don’t mess this one up Jim!), and then finally picking up the swag bag.

The swag bag has what you need to organize your clothes and supplies for each event. This is critical, and requires serious thought. For me, it means visualizing the race and selecting what I’ll need and exactly when I’ll need it, given the day’s weather conditions.

You get a five color-coded bags: one for your street clothes in the morning, one for T1 (when you change out of your wet suit), one for T2 (when you change out of your bike clothes), one for Bike Needs (what you think you might want at the half-way point in the bike ride), and one for Run Needs (what you might want at the half-way point in the run). I typically overpack my needs bags, so I have a little smorgasbord that I can choose from, according to how I feel at that point in the race. I spend 2-3 hours getting everything together, because once you’ve done it you’re committed. If you forget anything, you’re screwed. Got your swim goggles? Your run socks? Body Glide so your neck’s not rubbed raw from the wetsuit? Do you pack chicken broth (which has fat) or vegetable broth (which is just salt and water)? How much solid food will you really need? Because it becomes more difficult to digest as the race progresses. So there is a lot to think about. And as you go through the process, the anxiety and excitement increase.

The race isn’t until Sunday, but everything needs to be dropped off in the transition area on Saturday. But first I made a late decision to have a bike computer installed. For the first time I’ll be riding a true triathlon bike, a Cervelo P2C. I’ve been very hesitant about using it. It’s a totally different riding experience, a very fast riding experience, with a much greater risk of crashing. Steering in the aero tuck position is much more “twitchy.” The balance is “knife-edge.” Make a mistake, hit a rock or pothole wrong, or touch wheels with another cyclist, and you may find yourself on the ground. Until I put the bike on the car when I left home, I hadn’t really committed to riding it. But here I was, and it was the bike I’d be riding. And I really needed to know how fast I would be going. Fortunately there’s a bike shop in Penticton that is prepared for my “wait till the last minute” type, and they installed it in an hour at no extra cost.

With that done, and all the decisions behind me, Julie and I carried everything over to the area secured for the participants. The first thing I unloaded was the bike. These races are so well organized that your spot on the bike rack is clearly labeled with your name and race number.

Next up was the drop off for the Bike to Run. Here, as with the Swim to Run, everything is clearly laid out so that it can be quickly located during the race.

Now all that’s left is to wait out the day and the night. And that seems to take forever. During the day, you deal with the conflicting urges to run or jump on the bike, while at the same time knowing you need to to stay calm and conserve your energy. At night you wake up every hour, wondering how much longer until your 4:30 wake up call. I felt confident that my body was trained and rested for the event. My greatest concern was how I would handle nutrition and hydration during the race. The Ironman has a far greater investment both in time and money than any other event I do. And all that training could be wasted if I didn’t eat or drink sufficiently at the correct times. And nutrition isn’t something you can necessarily force your body to accept. So I still had plenty to be concerned about. It was a long day.

Eventually the time arrives. It’s 4:30am, and time for breakfast. I set up a little buffet of yoghurt, my homemade granola (get my recipe here), banana, peanut butter. And starting now, it’s time to drink plenty of water. I eat as soon as I wake up, so I have more time to digest before the race starts. After eating, I take my time getting ready. I’m still thinking about details, trying to time my morning so I don’t get to the swim start too early and end up standing around getting cold and nervous. But I don’t want to be late, and waste energy rushing around, looking for the volunteers who mark your body with your age and race number and the drop off for my street clothes bag. I rush from the hotel to the race start, am passed by a racer in tears who’s lost, and arrive in plenty of time for the 7am start. There’s so much activity, and so much the racer is responsible for, that it’s hard to think clearly.

The one thing you keep for race day is the wetsuit. That’s what you take with you in the morning. I always wait as long as I can before putting it on. It’s not comfortable. It’s very tight, so there’s a certain fatigue just wearing it. It gets hot and sweaty inside, it’s the feeling you get when you have the flu. And once you have it on, good luck if you have to pee.

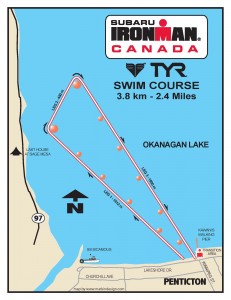

The swim is the most exciting of the events. And this was a bit more exciting because Lake Okanagan is home to the mythical 50-foot serpent Okopogo, Canada’s version of the Loch Ness monster. But seriously, it was the largest Ironman mass swim start ever, with nearly 3000 people, running into the water until they could run no farther, then launching forward, arms flailing and legs kicking. You really can’t see a thing, so you swim over others, hitting and kicking, or being hit or kicked by others. Then the wind picks up a bit and the shallow water near the shore gets very choppy. It’s chaos, but it’s a great feeling. For months you’ve been visualizing the race. Now it’s reality – you’re finally racing.

Soon you just settle in to the event. Your stroke evens out, your thoughts now are focused on the turn-around buoys. Then you’re at the furthest buoys and you focus on the swim finish. I enjoy open water swimming much more than pool swimming, just as I enjoy running on trails much more than around a track.

The swim is by far the shortest of the events. It’s soon over, you’re out of the water. After crossing the timing mat, I accept the offer of two volunteers to have them rip off my wetsuit. It’s amazingly fast and efficient when they do it. It would take me 5-10 minutes of struggling, and I’d be exhausted afterward. Then I’m off to the changing tent with my transition bag, given to me by a volunteer. Once I have on my biking shoes and jersey, I exit the tent where I’m given my bike. It’s a quick jog over to the timing mat, and then I hop onto the bike for 112 miles of biking.

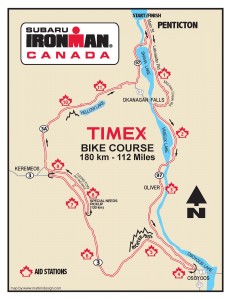

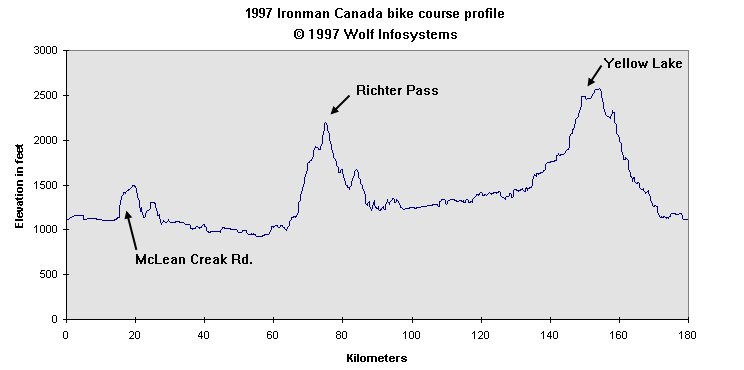

The start of the bike is exciting because the street is lined with cheering crowds. The biking lane narrows, so there’s a bit of jostling and cursing as faster riders pass. This is a good place for a slow, dangerous crash. Slow crashes are risky because you’re more likely to land on your head. Fast crashes more often result in a skid across the pavement, painful but more easily healed. The ride starts with a nice 10 mile ride along Skaha Lake. Then there’s a climb up McLean Creek Rd. Except for this stretch, the entire community has been very supportive of the event, and very nice to all of us. But someone out here doesn’t like us. They’ve scattered tacks on the road, and there are a dozen riders repairing flat tires. I make it thorough without damage, but am cautious for the next few miles. I hope the pros made it through OK, because racing is how they make their living, and a flat tire can mean the difference between winning and losing.

There’s a nice downhill stretch to Vaseux Lake and Highway 97, which gives me a chance to get comfortable with the speed of my triathlon bike. It’s followed by a relatively flat stretch of about 30 miles to the intersection at Osoyoos. This section of the ride is through vineyards and orchards. It’s also a fairly heavily traveled road, so much of it required riding single file.

At Osoyoos, the course turns away from the lakes, and onto Highway 3, which takes us up to Richter Pass, the first of the two big climbs. Fortunately, I’d just done the Death Ride about 6 weeks earlier, so I was ready for the hills. I maintained the aero position on the climbs and I raced as fast as I could on the descents. The stretch between the first climb at Richter Pass and second climb at Yellow Lake is very pretty. Pretty enough that the government is considering turning it into a national park. Hand-painted signs on the road indicate it’s an idea that’s not popular with the residents of the area.

The next 45 miles is the hottest part of the race. Much of it is an “out and back” loop, where you’re facing riders completing their loop. There’s not much of a breeze and the aid tents are running out of water. During the ride up to Yellow Lake I pass a dozen riders who have stopped and retreated to whatever shade they can find. All the ambulances seem to be occupied. I stop at one aid tent to get water but they are totally out. I stop at another and they are also out of water. Fortunately they have ice. I manage to fit some cubes into my water bottle. It’ll be another 10 to 20 minutes before it’s melted, but it will be nice and cold.

Overall, I’m luckier than most. I’ve stayed hydrated when there was water. I sipped every 5-10 minutes from the water bottle mounted to my aero bars, generally going through a quart of water every 10 miles. So the last 15 miles of the race are difficult, but I make it through OK.

From the top of Yellow Lake it’s mostly downhill to Highway 97 and Skaha Lake, then a relatively flat ride returning to the transition area for the start of the run. There’s a lot of road work being done on this stretch, so it’s the least attractive until the top of the pass. But then the view is very pretty and very welcome. I keep a good speed down to Skaha Lake, and then ride through town to the second transition.

By now I’ve been racing for over 8.5 hours and I’m sick of the heat and the sun. So I spend far longer in the transition tent than typical. I should be out in less than 5 minutes. After all, I’m only changing from my bike jersey into a running singlet and putting on my running shoes. Instead I take over 18 minutes. I know what I’m doing; I just don’t want to see the sun and feel that heat on the road. So I just sit in the tent and work on mentally preparing myself for a 26.2 mile run. (Yes, that 0.2 mile is important to runners. They say the first 20 miles is the first half of the race, so 0.2 miles is a good percentage of the second half of the run.)

I finally accept the fact that I can’t stay in the tent forever, as attractive as that may sound. I stop thinking and start moving. I stand up, turn to the exit, and start walking. As soon as I’m in the sun, I quicken my pace. The faster I move, the sooner I’ll be done. Just before crossing the timing mat to start the run, I have myself slathered in sunscreen by the volunteers. I grab a bottle of water to start the run with. I’m actually feeling good, but It’s HOT!

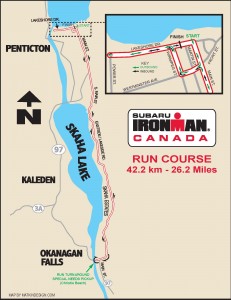

The course starts with a loop through town, so you can get motivated by the thousands of spectators. I keep up a good pace through town, hugging my water bottle. There are plenty of aid stations along the way, and they have no shortage of supplies. But having my own water means I can drink when I want. I keep up a good pace for the first 5 miles.

At the aid station at mile 5 I stop for a slice of orange. A couple of hundred yards past that, I stop to puke. I know it’s going to happen so I have time to pick my place. Fortunately I see a fire hydrant with no spectators nearby. Perfect! I lean over and let loose. I hear a few nearby spectators groan. A runner asks if I’m alright. I thank him, and let him know I’m fine.

And really I am fine; this is just part of the learning process. During the bike ride, I had a bottle of water 5-inches in front of my face, and I sipped from it every 5 minutes. But when the water was gone, and during my time in transition and the start of the run, I haven’t been as good about drinking water. After 9 hours of racing in the heat, digestion is very difficult. Without water it’s even more difficult. And that’s what I’ve learned. I can’t wait to remember to drink. Next time I need to set my watch alarm to beep every 5 minutes, so that I’m programmed to drink.

So far, my nutrition has been PowerBars, Gu, and 2nd Surge. All include electrolytes, protein, and carbohydrates in easily digestible form. I was relying heavily on the 2nd Surge chocolate and double espresso, which have the highest caffeine content of any gu I could find. It’s 100mg, which is one-fourth the caffeine of a Starbucks coffee. I’d made the decision to include caffeine after Ironman Coeur d’Alene, where I’d started the run totally drained. Not physically exhausted; but very sleepy. My decision seems to have been a good one, as I seemed to have plenty of energy throughout this race.

Unfortunately, at this stage of the run my stomach is still sending strong signals that I should slow the pace. I alternate between running and walking. At the turn-around at Christie Park in Okanagan Falls, I pick up my run special needs bag. It’s all the goodies that healthy Jim the day before had thought exhausted Jim might want. Most of what I see in the bag makes me slightly sick. What I do grab is a running bottle filled with vegetable broth and more 2nd Surge gu. I walk a bit, since it’s uphill at that point. And then I start the run back to the finish. As the sun starts to set, my pace picks up. As with my previous Ironman, the last 6 miles I run at a good pace. I am actually able to sprint the last quarter mile to the finish.

After marathons and Ironman distances, I’ve learned to go directly to the massage tent for recovery. One of the consequences of these events is that the blood pools in the legs, decreasing the blood available to the brain. This can result in collapse, and explains why I’m more affected by mental exhaustion than by physical exhaustion. Once I got the massage, I felt much better. It seemed like a long walk back to the hotel, and I needed to lie down with my feet above my head to recover. But after about 15 minutes I was feeling good enough to eat. My perfect post-race meal, given that I’m not in the mood to go out for dinner, has become sliced turkey, bread, and a quart of milk. By next morning I felt fine.

So in retrospect, how do I feel the race went? Fine. In fact, great, when I factor in the temperature. I was told the recorded temperature was 98-degrees, to which I’m sure you can add a few degrees for the asphalt road surface temperature. Ironman ranked it one of the 25 toughest Ironman events ever. (And yet Mary Beth Ellis broke a 21-year Women’s course record!)

What I’m most happy with is my bike time, which was about 27 minutes faster than Ironman Coeur D’Alene. And this bike course was tougher. I’m giving credit to my choice of my Cervelo P2C tri bike over my Bianchi road bike. The Cervelo is a true triathlon bike, with the aero frame design. It was a risk, because I’d only just bought it a few months earlier. It requires learning a new riding position, low to the frame. Until you get used to it, it’s hard on the lower back.

It was also risky, because it requires resting your elbows on the aero bars, making it much more difficult to steer. There is also the issue of braking. These bikes are built for speed, so the gear shifters are mounted on the tip of the aero bars where your fingers are. The brakes are mounted on the bullhorn handlebars. You can make quick adjustments to the gears, so you maintain maximum speed. But if you suddenly need to slow or stop, you must sit up and reach for the brakes, severely limiting your reaction time.

For all those reasons, steep downhills were seriously intimidating. The day before the race, Julie and I had driven the bike course, and both Richter Pass and Yellow Lake Pass have long steep descents. I was seriously worried that I’d brought the wrong bike. As it turned out, my top speed on the downhill was 43.6 mph. Fortunately, during the race adrenalin overtakes caution. And having done the California Death Ride just 6 weeks earlier, my bike handling skills were sharp, giving me the ability to go fast on those downhill stretches.

I also added another skill to shave a few minutes from my bike time. For the first time, I didn’t stop to pee. (Actually, I stopped once, waited in line 5 minutes, then said screw it and took off riding again.) Good thing, too, because I had my water bottle mounted between the aero bars so I was drinking every 5 minutes. Lots of peeing, no dehydration.

Other than the bike downhills, I was most worried about the run. Running is what I do best. But at my previous Ironman in Coeur d’Alene, I’d started the run with no energy. All I wanted to do was lay down on the grass and sleep. My legs felt fine, but I had no energy. It was a terrible feeling. This time I felt much better, so I was surprised that the run took me nearly as long as at IMCDA. But I’m not too disappointed, since my age group ranking was quite a bit better. My guess is that the heat was the determining factor.

My swim, as always, sucked. All I can say is that I’m still trying to become a better swimmer. The good news is I can swim 2.4 miles with no problem. The bad news is that it takes me 30 minutes longer than it should. It’s hard to imagine shaving 30% off my swim time, but it’s nice to have goals.

But the big question is: How did I do in my new age group? I placed exactly mid-way overall, which was 32 out of the 64 participants in my age group. And best of all, I felt OK, considering what I’d just done.

One last note: Another tradition has become the post-race meal. The next day Julie and I went to an upscale restaurant, the Hooded Merganser, for an excellent steak dinner. It’s built over the water, and while we were eating Julie saw this creature that we thought was a rat. It wasn’t much bigger than one. We were told it was a beaver. I’d like to believe it was.

So that’s it for Ironman Canada, and the heavy training program I started last December. In a few weeks I’ve got my last event for the year, the Alcatraz Invitational Swim, which will be the subject of my next blog.

When Jim is not training for or participating in endurance events, he is the owner of Phoenix Technical Publications. Phoenix Tech Pubs has provided complete technical writing and documentation services in the Silicon Valley for over 25 years.